I - Intersections between architecture and mental health

On the psychological constructs of space

In the realm of environmental psychology, the exploration of the myriad relationships between humans and their environments is guided by what are termed ‘psychological constructs of space.’ These constructs are deeply rooted in the fundamental nature of our species, providing valuable insights into how they manifest within the context of this study.

Environmental Psychology identifies various points of intersection between the individual and the world, highlighting the dynamic interplay between them. This perspective provides a plausible starting point for analyzing one such intersection—the influence of the environment on humans. The study begins with a broad overview, progressively moving towards more detailed examinations to address the research questions effectively.

Humans are inherently perceptive beings, and perception serves as the foundation for our daily experiences, shaping how we interact with the world around us. Our senses gather information from physical spaces, allowing us to build a rich and complex understanding of our environment. This perceptual ability not only aids in navigation and survival but also significantly influences our emotions, thoughts, and behaviors. Within the framework of psychological constructs of space, perception and cognition are central, mediating the relationship between individuals and their environments by affecting how we interpret and respond to spatial stimuli.

Environmental Psychology identifies various points of intersection between the individual and the world, highlighting the dynamic interplay between them. This perspective provides a plausible starting point for analyzing one such intersection—the influence of the environment on humans. The study begins with a broad overview, progressively moving towards more detailed examinations to address the research questions effectively.

Perception and cognition

Perception and cognition play a crucial role in how we interact with our environment, particularly within the field of environmental psychology (EP). Traditionally, perception has been defined by Aristotelian concepts as a conscious experience derived from sensory information processing. However, recent research suggests that perception is far more complex. This complexity isn't about its magnitude but rather its essence—current explanatory systems still fall short of fully capturing the phenomenon.

The perceptual-cognitive system is now understood as part of a broader information processing system, where activities once thought exclusive to cognition are increasingly seen as integral to perception. Sensory experiences are influenced by individual characteristics, including personal values. This shift in understanding necessitates considering the environment as an active participant in perception studies, moving beyond the traditional object-centered view. The distinction between object and environment becomes blurred as we recognize that humans don't just observe their surroundings—they participate in them.

Kevin Lynch’s concept of cognitive maps, introduced in The Image of the City, illustrates this interaction between perception, navigation, and memory in urban spaces. Cognitive maps, shaped by the legibility of symbolic landmarks and influenced by mental images, guide behavior in space, often subconsciously. This concept is essential for understanding how individuals interact with their environments, forming behavioral patterns based on past experiences and present perceptions.

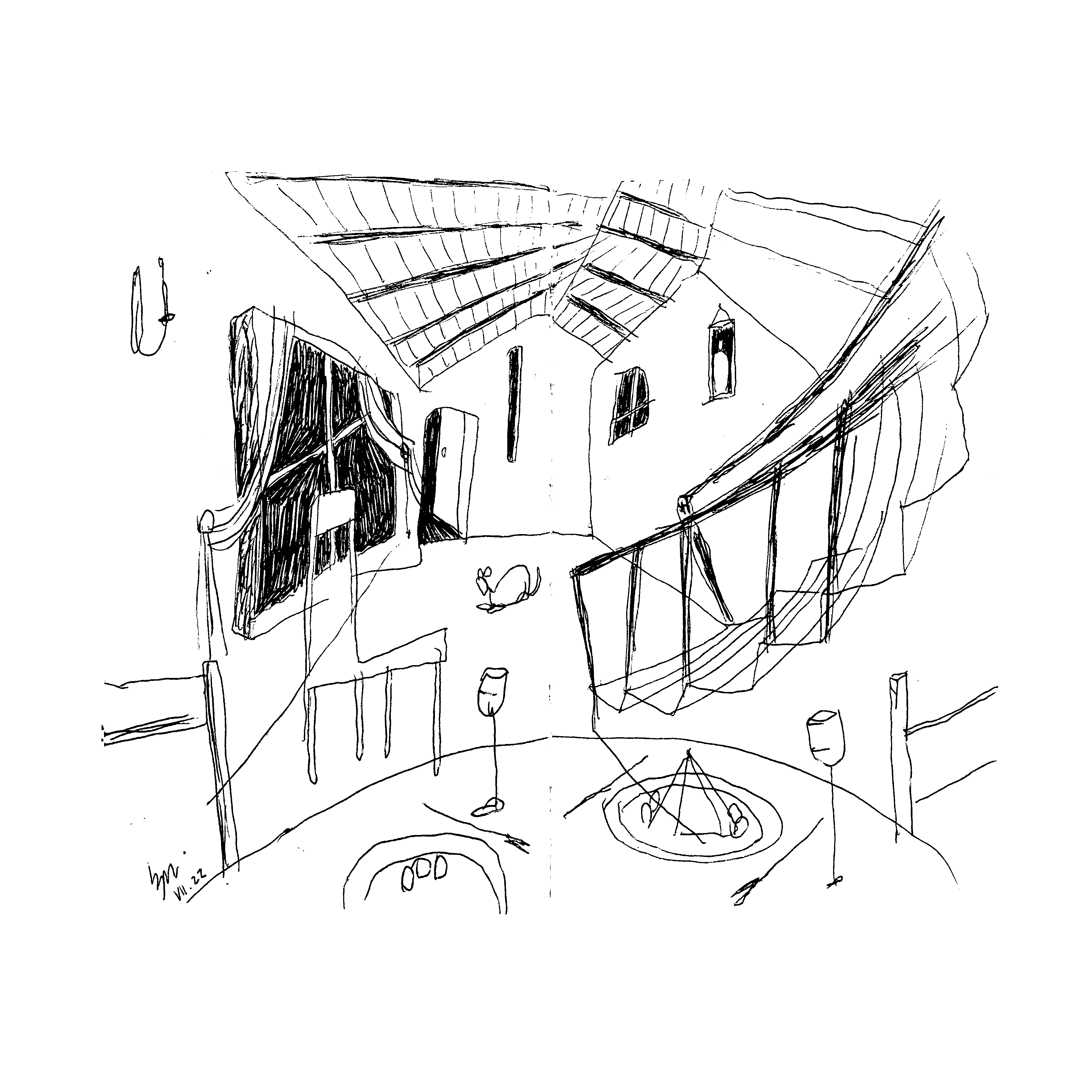

For psychiatric architecture, understanding perception is key to creating spaces that promote patient integration and autonomy. Functional design, privacy, and symbolic landmarks within a building can significantly influence how patients navigate and interact with their surroundings. Flexibility in space design, including responsive elements like doors and windows, is crucial for managing crises and promoting a sense of control. A non-responsive environment can lead to feelings of helplessness and restlessness. The interaction between humans and their environment is reciprocal, with both actively shaping each other. The term "transaction" captures this dynamic, emphasizing that individuals and environments are not separate entities interacting unidirectionally but are deeply interconnected.

i. the environment is perceived holistically;

ii. individuals’ environmental characteristics are intertwined with social systems;

iii. interaction with the environment often occurs at a less conscious level, influenced by affective factors;

iv. the environment is cognitively organized into mental images that facilitate communication;

v. the environment holds symbolic value, reflecting objective, affective, and socio-cultural dimensions.

ii. individuals’ environmental characteristics are intertwined with social systems;

iii. interaction with the environment often occurs at a less conscious level, influenced by affective factors;

iv. the environment is cognitively organized into mental images that facilitate communication;

v. the environment holds symbolic value, reflecting objective, affective, and socio-cultural dimensions.

Stimuli for spatial friction

When introducing the second psychological construct, it is important to begin by considering the significance of clarity and the understanding of built forms, as ambiguity in these forms often proves to be an obstacle. Ensuring spatial coherence allows users to make accurate deductions about the character, purpose, and location of a space. In contrast, poor programmatic organization can obscure patterns between spaces and introduce unclear signals regarding appropriate behaviors. Such ambiguity in spaces tends to induce stress in users because it impedes their ability to make functional sense of their surroundings, demonstrating how the perception of certain spatial stimuli can create friction.

In the research and literature review, it becomes evident that the primary intention behind the design of psychiatric spaces is to reduce stress and promote tranquility in individuals undergoing treatment. The calmness of a space supports the patient’s internal balance and aids in processing the adverse conditions of their mental instability. However, it is well understood that both calm and restlessness are intrinsic aspects of the human condition, characterized by psychological and physiological expressions.

Stress is particularly prevalent among individuals diagnosed with mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders (MBNDs), making it a clear indicator of friction within a space. Characteristics of friction-ridden spaces include physical hostility, decision overload, and the functional inadequacy of spaces lacking proper socio-psychological signals. Notably, excessive stimuli (such as noise, temperature fluctuations, and light variations) can trigger stress in disorders requiring precise regulation, like PTSD and schizophrenia. Conversely, the absence of stimuli can also induce stress, as it deprives individuals of the quasi-normal experiences needed to face challenges with a degree of adversity, which is crucial for conditions like anxiety and chronic depression.

“The issue for environmental planning is not to create environments in which stress is entirely absent, but rather to attempt to selectively limit the amount and types of stress the user of an environment must experience.”

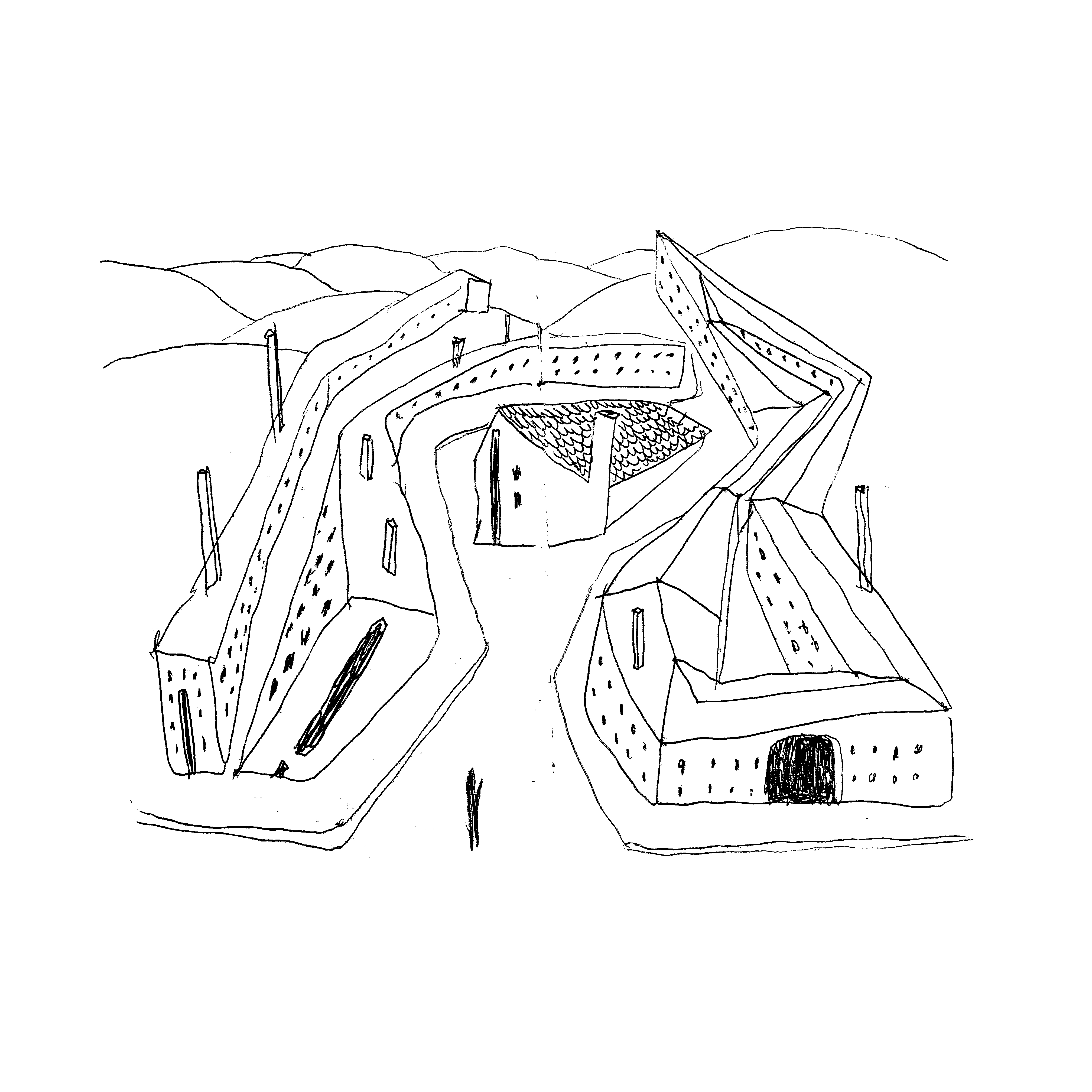

While friction-filled spaces can induce stress, they should not eliminate the human ability to adapt. Therefore, the idea of creating spaces completely devoid of challenges is unrealistic. A balanced application of these aspects gives a space character and offers opportunities for self-improvement and personal development. As Swiss psychiatrist Carl G. Jung aptly stated, “Man needs adversities; they are necessary for health. What concerns us here is just too many of them.” In summary, three principles are suggested for designing environments with a calibrated level of stimuli:

i . Consider the human scale: Access the diverse needs,activities, and capabilities of potential users. The design and planning of the space should reflect this diversity, ensuring it can adapt to various uses and functions.

ii. Offer variety and flexibility: Provide different environments that are easy to access and move between. Avoid consolidating all functions in a single space. Instead, offer quiet areas for relaxation and stimulating spaces for engagement, presenting them as separate but equally accessible options.

iii. Prioritize coherence: Design environments that are clear and easy to navigate, minimizing cognitive strain and enhancing the quality of attention. The space should be intuitive and user-friendly, ensuring that its adaptability and functional flexibility do not overshadow the need for intellectual stimulation and aesthetic care.

Cultural notions of aesthetics

Cultural aesthetics profoundly shape the environments humans create and inhabit, influenced by a deep-rooted appreciation of beauty alongside intellectual and technical skills. This cultural framework, comprising shared customs and symbols, guides behaviors and habits within a group, and aesthetic preferences play a significant role in this system, reflecting our species’ primordial origins.

In environmental psychology, the importance of scenic qualities and aesthetics in design is increasingly recognized. These factors are crucial in creating spaces that consider both cognitive and emotional responses. Two main perspectives emerge: one that sees aesthetic preference as a reasoned, cognitive choice based on perceived value, and another that views it as an emotional reaction to the properties of stimuli. Both perspectives highlight the need to understand how cognition and affect interact in shaping preferences, with evidence suggesting a reciprocal relationship between these aspects.

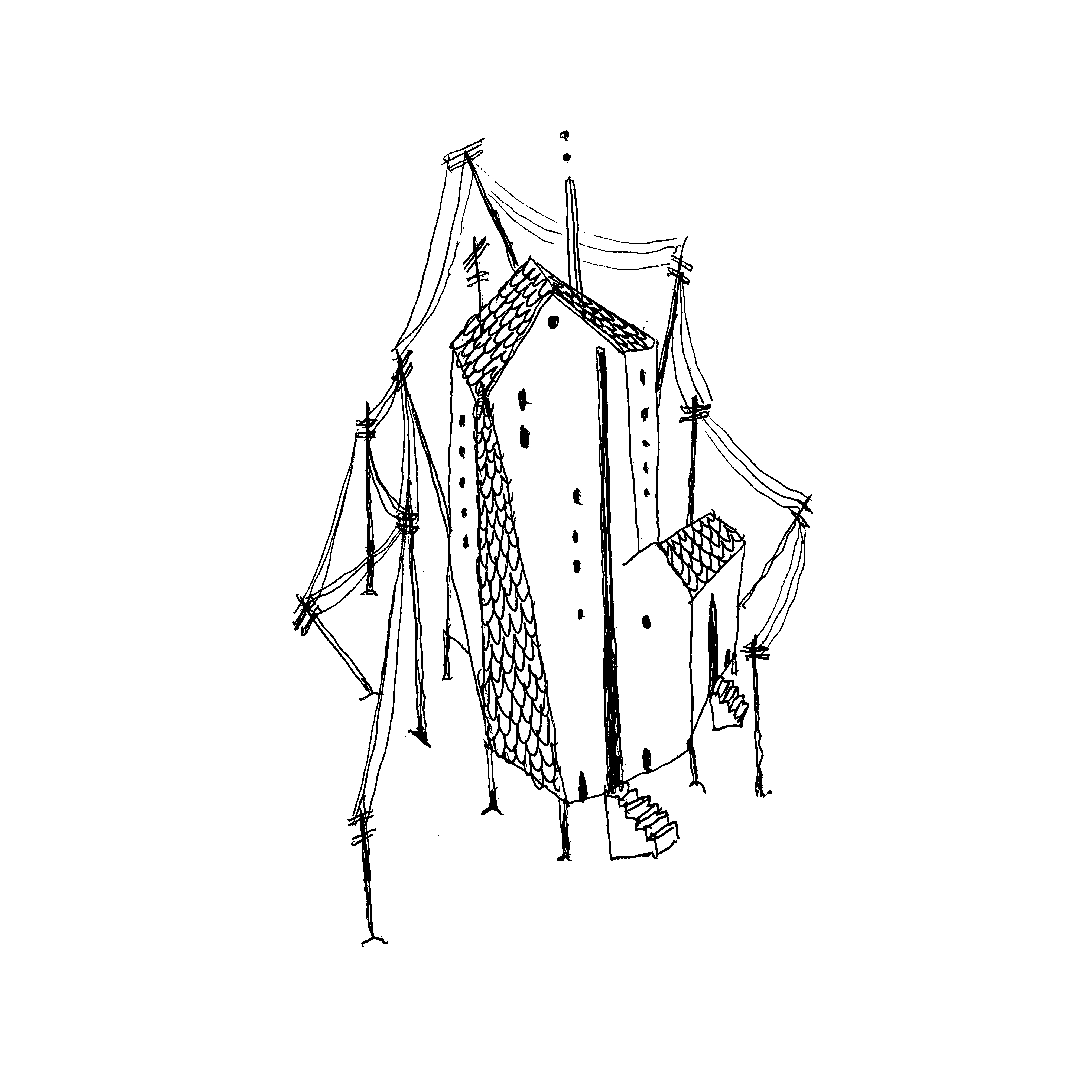

This analysis serves as a bridge between constructs driven by cognitive functions and those influenced by emotional affect. In designing therapeutic spaces, it is essential to move beyond merely eliminating spatial friction and consider how aesthetics can elevate the environment to nurture the human spirit. Meditative practices and religious spaces demonstrate how beauty and balance in design contribute to mental recovery, suggesting that aesthetics should be carefully considered in therapeutic settings.

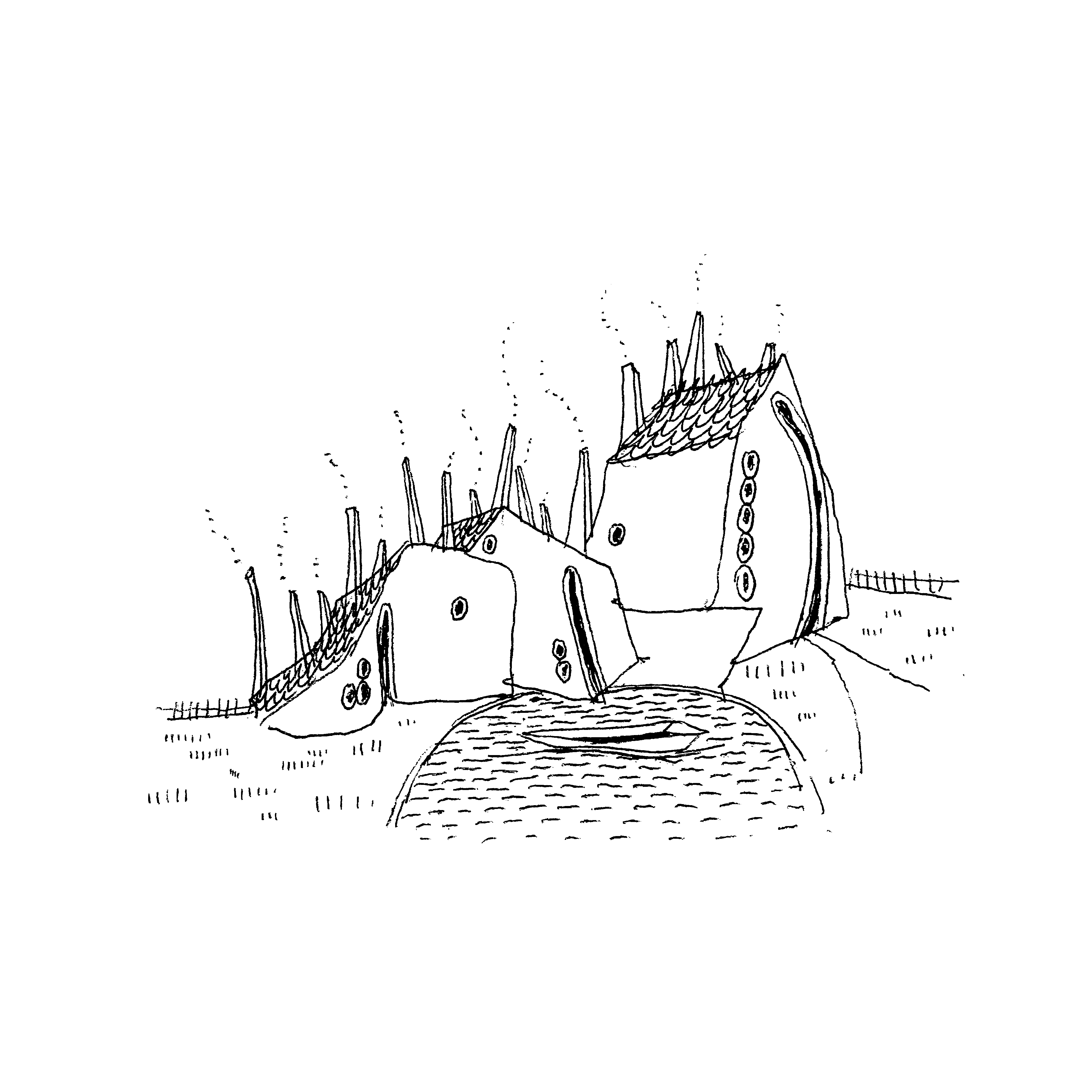

The aesthetics of space should be sensitive to cultural contexts. For example, Japanese writer Tanizaki highlights the importance of softer, culturally resonant tones in hospital settings, illustrating how cultural preferences influence the interpretation of raw materials and their aesthetic treatment. This aligns with the idea that high levels of material processing can strip away their natural qualities, while lower levels preserve their intrinsic character, contributing to a deeper, collective appreciation of beauty.

Research in Environmental Psychology supports the notion that natural environments have strong restorative effects, emphasizing the relationship between psychological and ecological factors. Vitruvius' concept of venustas, which links beauty to the order of nature, underscores the importance of proportion and symmetry, suggesting that design should harmonize with the human form and its surroundings. This balance reflects a deeper aesthetic sense that transcends culture and contributes to creating a therapeutic, uplifting environment.

The design of therapeutic spaces should reflect a harmony between natural laws and human experience, aiming for eurythmy—a graceful and pleasant atmosphere that aligns with the timeless principles of beauty. Vitruvius reminds us that while nature provides the foundation, human expression and art must refine and enhance this natural beauty, creating spaces that not only heal but also elevate the human spirit.

Sense of belonging

The sense of belonging in a place develops when individuals connect with it as an integral part of their identity. This connection, both personal and communal, is especially significant during prolonged interactions with environments, such as hospitalization in psychiatric institutions. As individuals engage with their surroundings, their sense of identity is shaped by that environment. If nature has restorative qualities that transcend cultural interpretations, it is plausible to consider that these aspects, rooted in our species' distant past, can also foster a sense of belonging and attachment to place.

The concept of proxemics explores how humans use space and defines the relationships between physical distance and interaction. One aspect, infraculture, pertains to behaviors rooted in the early origins of our species. This concept aligns with the deeper, often unconscious connections individuals feel towards natural environments. In crafting 'artificial' elements, the degree to which natural materials are altered reflects cultural values, which in turn influences the sense of belonging. If a culture highly values nature, it will likely preserve the original qualities of materials, fostering a stronger infra-cultural connection.

Architectural design plays a crucial role in this process. When materials are used in a way that retains their natural state, individuals, particularly those with mental and behavioral disorders, may find it easier to assimilate and feel connected to the space. The cognitive and emotional perception of a space can be further influenced by thoughtful use of color and light, which can enhance the sense of belonging.

Research also shows us that a sense of belonging in nature leads to positive mental health outcomes. Moreover, active participation in sustainability and environmental preservation efforts significantly enhances well-being. This final construct emphasizes the relevance of fostering a sense of belonging in natural environments, especially in the context of the current environmental crisis of the Anthropocene era.

Eco-psychological awareness

Eco-psychological awareness recognizes the mutual impact between humans and their environment, where each influences the other in a true ecological sense. This concept is particularly relevant in the context of environmental pride, which can enhance an individual's sense of belonging and, consequently, their mental well-being. This awareness has gained prominence alongside the green movement, which advocates for environmentally responsible and sustainable architecture. The evolution of eco-psychological awareness reflects a growing recognition of the imbalance between human behavior and the natural environment, signaling the beginning of a new era in environmental psychology research.

Understanding the connection between a sense of belonging in nature and positive environmental behavior is crucial. This connection appears to stem from an expansion of identity—when individuals feel closer to nature, their empathy and willingness to engage in pro-environmental actions increase. This aligns with value-based models that suggest people who integrate the environment into their sense of self are more likely to engage in environmentally significant behaviors. Eco-psychological awareness mediates this relationship, highlighting how interconnectedness with nature can inspire a sense of responsibility toward the environment.

A transactional approach to this relationship unifies psychological processes and environmental sustainability, recognizing their interdependence. The multidimensional nature of environmental ecology—spanning local and global, physical and mental, individual and collective dimensions—requires a holistic approach that fosters sustainable behaviors while improving human well-being. The interdependence between human behavior and environmental consequences emphasizes the importance of eco-psychological awareness.

In conclusion, the growing relevance of eco-psychological sensitization is evident in practical cases that illustrate its effectiveness in designing spaces for mental recovery. This awareness is increasingly recognized as a vital component of promoting both environmental sustainability and mental health.