I - Intersections between architecture and mental health

In the study of Environmental Psychology, various psychological constructs of space have been assimilated into architectural design, leading to the concept of Evidence-Based Design (EBD). This approach has become central in the field, marking a shift towards designs that are informed by empirical research on how spaces impact human behavior and well-being. This subchapter explores how these therapeutic principles guide the design and conception of healing environments.

Historically, architecture emerged from the instinct to create shelter as a defense against the external world. This act of creating a place for rest and protection contributed to the development of the human condition, including psychological aspects. Architecture serves as a mediator between the internal and external worlds, balancing basic architectural elements—floors, ceilings, walls, doors, and windows—to regulate the permeation of the natural environment into human spaces. Doors, for instance, control physical movement between spaces, while windows allow for different types of interaction with the outside world, such as light, climate regulation, and observation.

This analysis aims to establish a clear understanding of how such elements function within the broader framework of Evidence-Based Design, using paradigmatic examples to illustrate these concepts in practice.

Designing architecture to support therapy

In the study of Environmental Psychology, various psychological constructs of space have been assimilated into architectural design, leading to the concept of Evidence-Based Design (EBD). This approach has become central in the field, marking a shift towards designs that are informed by empirical research on how spaces impact human behavior and well-being. This subchapter explores how these therapeutic principles guide the design and conception of healing environments.

Historically, architecture emerged from the instinct to create shelter as a defense against the external world. This act of creating a place for rest and protection contributed to the development of the human condition, including psychological aspects. Architecture serves as a mediator between the internal and external worlds, balancing basic architectural elements—floors, ceilings, walls, doors, and windows—to regulate the permeation of the natural environment into human spaces. Doors, for instance, control physical movement between spaces, while windows allow for different types of interaction with the outside world, such as light, climate regulation, and observation.

These elements illustrate the interplay between interior and exterior environments, making windows - caesura - a focal point in understanding how architectural design can align with theoretical principles to create therapeutic spaces.

This analysis aims to establish a clear understanding of how such elements function within the broader framework of Evidence-Based Design, using paradigmatic examples to illustrate these concepts in practice.

Open-air hospital

Imhotep, the vizier of Pharaoh Joser, is recognized as the first architect in recorded history, known for designing the pyramid at Saqqara in the 27th century BC. Beyond his architectural achievements, Imhotep was also revered as a healer, earning comparisons to Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine. This dual expertise in architecture and healing underscores the historical connection between these disciplines in promoting human well-being. Our interest in the impact of architecture on mental health was first sparked by a preliminary study of La Ronchamp, which highlighted the role of architecture in influencing psychological states. Although EBD is often considered a modern concept, its roots can be traced back to the late 18th century in projects like the York Retreat, Bethlem Royal Hospital, and Hôtel-Dieu. Pioneers such as Philippe Pinel and William Tuke made early strides in linking environmental design to therapeutic outcomes.

One of the most emblematic cases of EBD is the Paimio Sanatorium, designed by Alvar Aalto in the early 20th century. This project was groundbreaking in its focus on patient-centered design, particularly in how it addressed the needs of tuberculosis patients. Aalto described the sanatorium as a "therapeutic instrument," integrating features like balconies for outdoor exposure, which was crucial for treating pulmonary diseases. The design of the Paimio Sanatorium exemplified how architecture could directly contribute to patient recovery, serving as a model for future therapeutic spaces.

Another noteworthy example is the open-air shelters designed by Snøhetta for the Friluftssykehuset foundation in Norway. Located near Oslo Hospital, these shelters aim to ease the hospital experience for patients and their families by providing a natural environment that supports psychological well-being. These shelters, made primarily of wood and facing the forest, create a seamless transition between the interior and the natural world, offering a restorative space that enhances the healing process.

In contrast, while visiting these shelters, it became clear that their design, although soothing, lacked the dual contextual openness seen in more research-driven projects like those by White Arkitekter. The shelters close off from the hospital, focusing entirely on the natural environment, which, while effective, does not fully explore the integration of both the clinical and natural contexts. This comparison highlights the importance of a comprehensive, research-informed approach to designing therapeutic spaces that address the complex needs of their users.

In the light of White Arkitekter

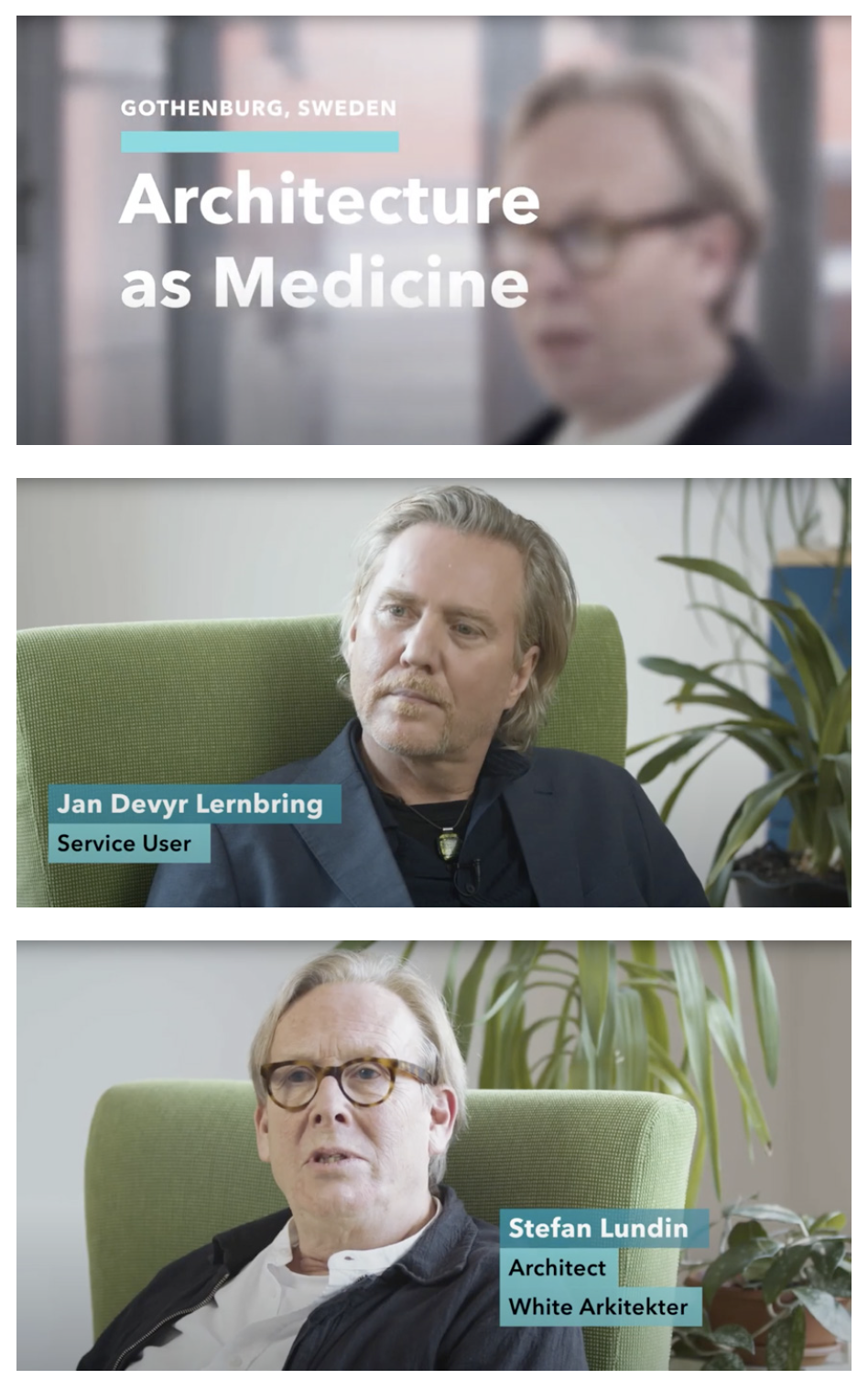

White Arkitekter (WA) is a prominent Swedish architectural firm known for its significant contributions to sustainable construction and the role of architecture in mental health. With a strong presence in Scandinavia, the firm has gained international recognition for its innovative approach to designing spaces that support mental well-being. My introduction to their work came through a webinar that analyzed a completed project and explored how its insights were applied to a new project with a similar purpose. The webinar began with a conversation between the lead architect of the original project and a former patient, underscoring WA's commitment to evidence-based design.

The seminar opened with a powerful statement: mental health is a fundamental human right and a key driver of social, cultural, and economic progress. Despite this, the stigma surrounding mental illness remains a significant barrier. WA emphasized the need to rethink the design of mental health spaces through co-participatory processes, where the insights of patients and healthcare providers are integrated into the architectural planning. This approach is particularly relevant in the new generation of psychiatric facilities, where the design of space increasingly plays a critical role in enhancing the effectiveness of mental health treatments.

One intriguing aspect discussed during the seminar was the placement of psychiatric facilities within their urban or social contexts. Two contrasting approaches were presented: one where the facility is integrated into an urban center, and another where it is more distanced from such environments. Both approaches have their strengths and limitations. The moderator highlighted that "one of the signs of a healthy society tends to be manifested in the feeling of cohesion and mutual help that it promotes." By reducing the stigma around mental illness, mental health treatment can be given the same dignity and respect as physical health treatment.

During the seminar, architect Stefan Lundi and former patient Jan Devyr discussed the Östra Psikiatri psychiatric clinic in Gothenburg. Jan praised the space for its beneficial features, including natural light, the use of textiles and calming colors, the sensory comfort of wood, and the healing presence of nature both inside and outside the building. However, he also offered some critiques. Jan noted that the long corridors could cause anxiety, particularly due to blind spots that hinder staff from performing their duties efficiently and reduce the overall sense of security. He also pointed out the lack of a reception lobby, which can negatively impact the feeling of safety and privacy for voluntarily admitted patients. This issue is especially pertinent given that this space is designed primarily for emergency admissions and post-triage care.

This discussion underscores the importance of carefully considering both the therapeutic and practical aspects of architectural design in mental health facilities. By incorporating feedback from those who have directly experienced these spaces, firms like White Arkitekter are helping to create environments that not only support mental health treatment but also promote a broader societal understanding and acceptance of mental illness.

Viewing nature through the window

In our journey to explore the intersection of architecture and mental health, we were fortunate to engage with Stefan Lundi, a distinguished architect at White Arkitekter (WA). Our initial contact was inspired by a genuine appreciation for his work, which we had first encountered through a webinar. Scandinavian culture's openness and linear hierarchy made it easy for us to find Stefan's contact information on the WA website, and after a brief conversation in Swedish, we introduced him to our research. Stefan responded with enthusiasm, generously offering his support and sharing essential references, including his own publications and the research of Professor Roger Ulrich, a renowned figure in the field.

Roger Ulrich's research, which is highly respected within the architectural and medical communities, emphasizes the significant impact that a window's view can have on a patient's recovery in clinical settings. Ulrich's findings align with the idea that what is observed through a window can act as a "caesura" between the external environment and the patient's mental state. His studies have shown that views of nature from clinical wards, where patients often spend extended periods, can lead to marked improvements in both psychological and physiological conditions. Ulrich's work confirms that natural views reduce stress, anxiety, high heart rates, and the need for painkillers, while also improving the well-being of healthcare workers by reducing work-related stress and increasing job satisfaction.

During our ongoing dialogue with S. Lundi, he shared an article co-authored with R. Ulrich that delves deeper into the stress-reducing aspects of spatial design, particularly focusing on the "view of nature through the window." Their research, based on controlled studies, demonstrated that patients exposed to natural views experienced reduced anger and stress, even in the face of provocative situations. This effect extends to healthcare workers as well, highlighting the broader implications of such design choices.

As our research progressed, we revisited the White Arkitekter seminar, which transitioned from discussing the Östra Psychiatric Clinic project in Gothenburg to a new project, Södra Älvsborg Psychiatric Clinic, located an hour away in Borås. This new project aimed to incorporate lessons learned from the Östra Clinic, addressing its shortcomings and improving upon them. Our interest in the window as a caesura led us to plan a visit to both the old and new clinics. Stefan, upon learning of our visit, kindly arranged a meeting where we received valuable feedback from him and Anders Jirås, a former photographer for WA. They both recognized the relevance of our research in the current era, where mental health issues are receiving increasing attention.

Following our visit and discussions, we received approval from the clinic's administration to conduct a photography project on site. We decided to focus on capturing a gradient of views from various rooms within the Södra Älvsborg Psychiatric Clinic, comparing those close to nature with those facing more artificial environments. This approach aligns with the logistical and conceptual frameworks of our study, providing us with a rich array of data to further explore the impact of architectural design on mental health.

Towards Södra Älvsborg

The design of psychiatric care facilities often challenges conventional expectations, as effective architecture in this field emphasizes continuity in everyday life rather than confinement. The best support architecture can offer to patients lies in fostering connections with nature, whether by providing unescorted access to gardens or simply allowing patients to view a tree from their window. This philosophy underpins the design of the Östra Psychiatric Clinic, completed in 2006, which sought to create a healing environment deeply intertwined with natural elements while meeting the unique requirements of a psychiatric institution.

Despite the inherent challenges of such a program, Östra successfully incorporated outdoor spaces while adhering to safety protocols. The clinic's design is a testament to the application of theoretical concepts like biophilia and spatial organization that encourage a closer relationship between patients and their environment. Special care was taken to ensure that every patient had visual access to natural elements, facilitated by the strategic placement of three central courtyards. These courtyards, positioned between departments, enable even centrally located rooms to benefit from natural views, thus encouraging patients to spend time outside. Moreover, patients have the autonomy to access these courtyards independently, which fosters a sense of control and the therapeutic benefits of outdoor exposure.

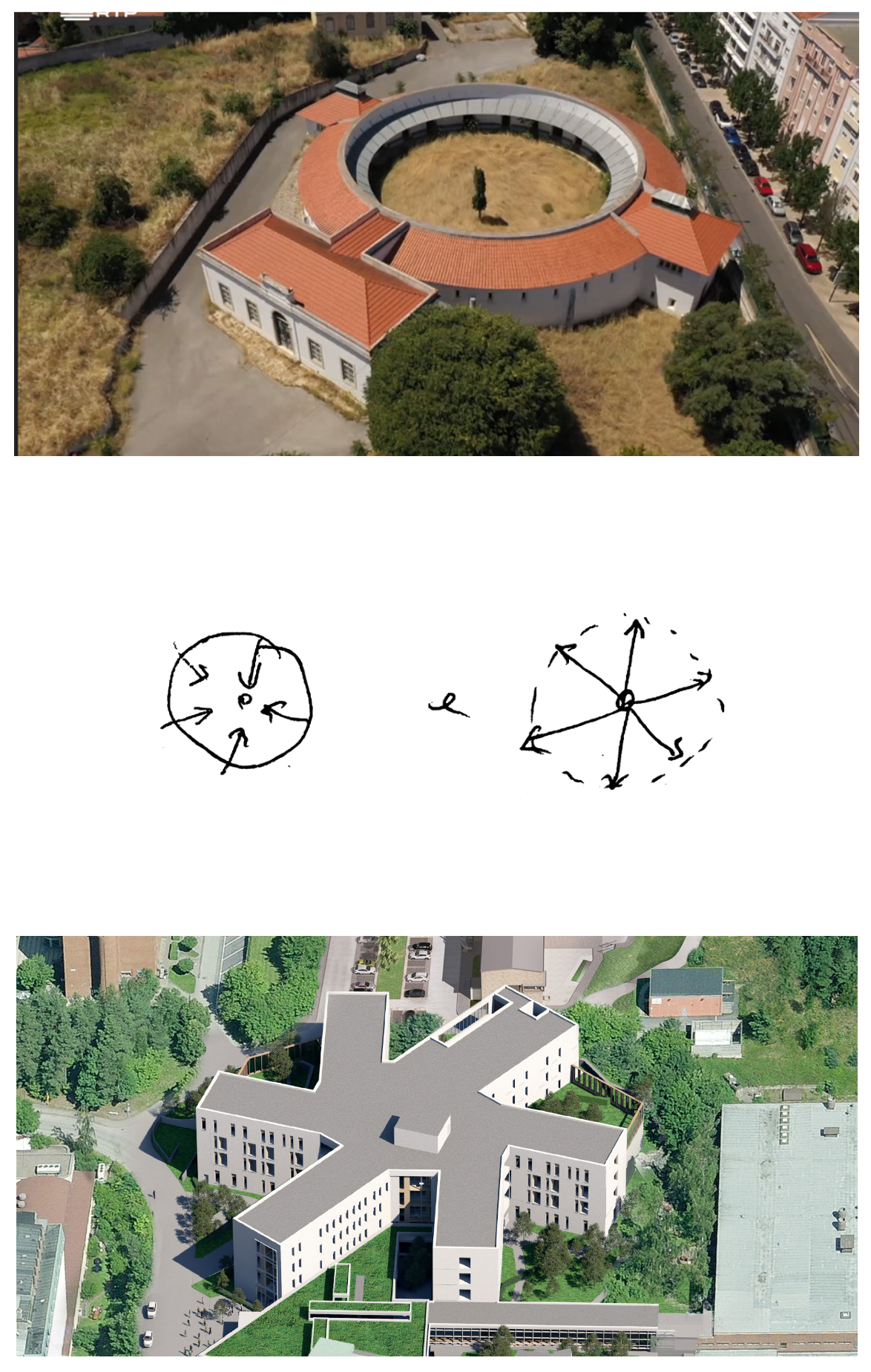

When we visited the Södra Älvsborg Psychiatric Clinic, a project that builds upon the lessons learned from Östra, we immediately noticed three distinctive features: an inviting reception area, a unique typological configuration, and a location more remote from urban centers. The welcoming reception area facilitated our interactions with the building’s management, and for voluntary admission patients, this openness provides significant relief. The typological configuration of the clinic was particularly intriguing. Unlike the more enclosed patios of Östra, Södra features patios that are only partially enclosed, allowing them to open directly to the surrounding environment. This design choice establishes a seamless connection between the clinic and its natural context. The Södra Älvsborg Psychiatric Clinic, situated away from urban constraints, was designed to be a dignified public building that does not feel like a closed institution. It includes wards for psychiatric rehabilitation, emergency, and pediatric services, as well as administrative offices. The design aims to promote independence, freedom, and autonomy for patients while providing a calm and safe environment for staff, family, and visitors. The clinic consists of two pre-existing buildings and two new ones, named the ‘Star’ and the ‘Square’. The ‘Square’ serves as the new entrance and connects to the old buildings via a glazed corridor, while the ‘Star,’ with its dynamic shape, adapts to the sloping terrain and opens to the surrounding natural elements, avoiding the institutional feel of long, monotonous corridors.

The choice of the ‘Star’ typology in Södra was not merely a formal decision but one deeply connected to its function. This typology was also explored in a psychiatric clinic in Helsingør, Denmark, built 14 years before Södra. Through our analysis, we observed that this design choice reflects a deliberate move away from the oppressive "Panopticon" typology—a design that symbolizes control and surveillance, leading to the denigration of the individual. In contrast, the ‘Star’ typology symbolizes the emancipation of patients, offering them a space that opens up to the surrounding environment and, in Södra's case, to the adjacent forest.

This typological choice is not just about aesthetics; it is grounded in evidence-based research that in this case could emphasize the therapeutic benefits of its nearby nature.

By integrating these principles into the design, Södra Älvsborg Psychiatric Clinic provides a space that not only meets the functional needs of a psychiatric institution but also supports the mental and emotional recovery of its patients. The architecture here is not just about containing patients but about empowering them through a connection with the natural world.