Introduction to the photographic narratives

Photography has become a powerful medium for capturing and accurately representing architecture, serving as a crucial tool for visual documentation. The widespread availability and mass production of images have allowed architectural photography to reach a global audience, complementing traditional publications in the field. This has established it as a reliable visual repository, offering a way to document structures and spaces with a level of rigor that drawings or engravings cannot always achieve. However, as James Ackerman notes, while photographs provide clues to their documentary reliability, they are not entirely transparent reproductions, especially in an era where digital editing can alter images.

The pursuit of realistic representation in visual art began in the Renaissance with the development of perspective drawing and was further advanced by the invention of the camera obscura. The earliest uses of this technique can be traced back to Ancient China around 400 BC, where the philosopher Mozi described how light passing through a small hole into a dark room would project an inverted image of the outside world onto the walls. This phenomenon laid the groundwork for the science of photography. Over time, objective lenses were incorporated into these devices, allowing for more precise image projections, and by the 17th century, portable versions like boxes and tents were developed for easier use.

The pursuit of realistic representation in visual art began in the Renaissance with the development of perspective drawing and was further advanced by the invention of the camera obscura. The earliest uses of this technique can be traced back to Ancient China around 400 BC, where the philosopher Mozi described how light passing through a small hole into a dark room would project an inverted image of the outside world onto the walls. This phenomenon laid the groundwork for the science of photography. Over time, objective lenses were incorporated into these devices, allowing for more precise image projections, and by the 17th century, portable versions like boxes and tents were developed for easier use.

The true advent of photography came with the discovery of techniques for fixing these images, culminating in Nicéphore Niépce's success in 1826. After a decade of experimentation, he captured the first heliographic image on a bitumen-coated tin plate through an eight-hour exposure. This image, depicting the view from his bedroom in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, marked the beginning of modern photography. Throughout the 19th century, rapid advancements made photography increasingly accessible, reducing the need for the manual skills of painters and making the process more mechanical and independent of the photographer's personal influence. As a result, photography became a fundamental tool for documenting and communicating architectural information.

As photography evolved, so did its use in architecture, growing in tandem with demand for faster and higher-quality techniques. This evolution led to a shift in photography's role—from merely replicating reality to exploring more artistic expressions. This shift is captured in the observation that "photography began to change into something else, a something which had lost interest in the unique connection between the inside and outside."

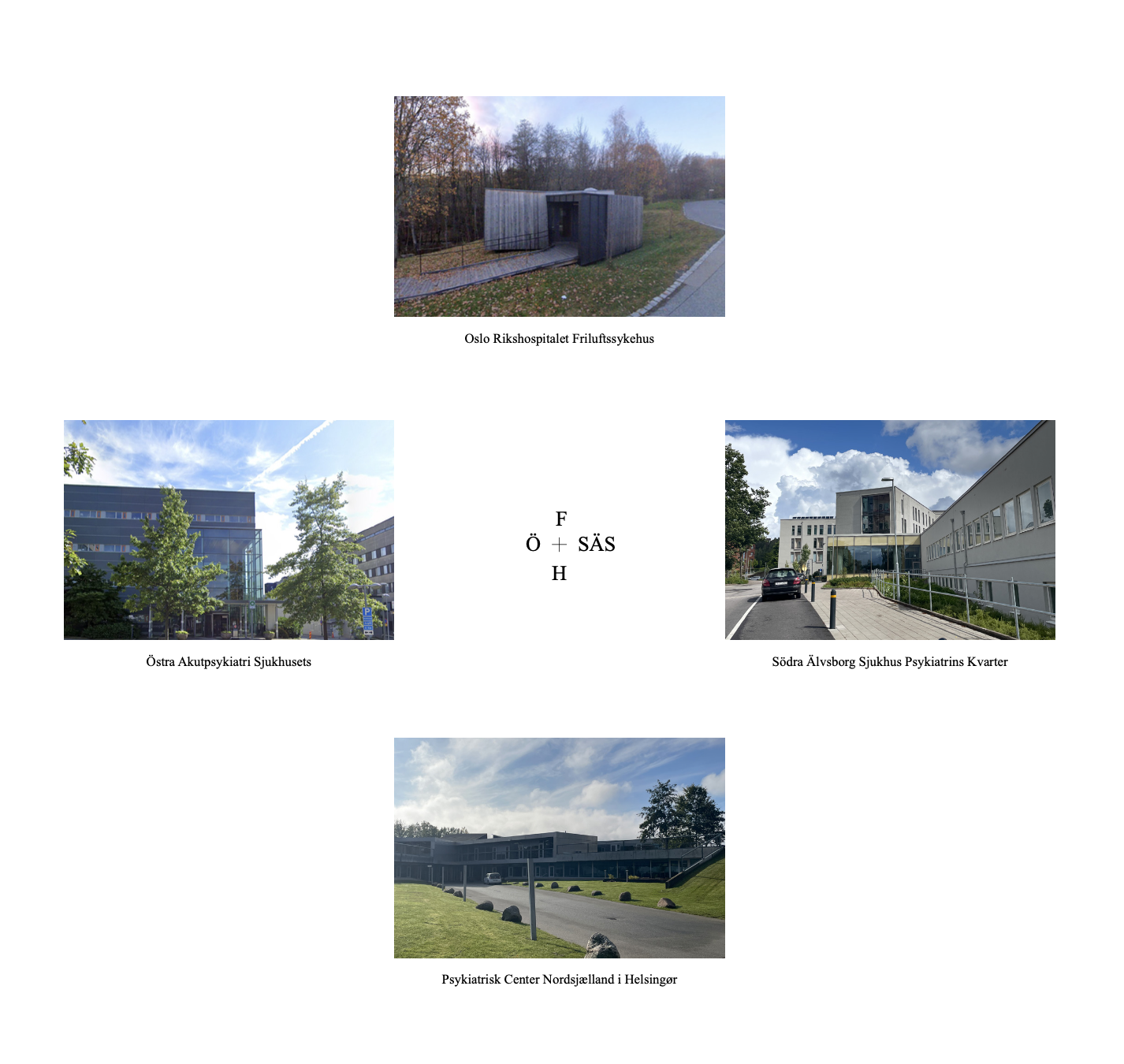

In the context of our study, the documentary approach to photography operates almost anonymously, producing images that serve as a future archive to illustrate the projects we studied. Using a smartphone's photographic device, we captured moments instantaneously, focusing on aspects like perspective orientation, framing balance, and distance from the subject. However, certain factors beyond our control, such as the date and time dictated by convenience rather than a consistent rule, indirectly influenced the final results. This archive proved useful when comparing different practical applications of the concepts studied in the works we visited, helping us clarify our intentions for the artistic exploration of Södra Älvsborg's project.

As photography evolved, so did its use in architecture, growing in tandem with demand for faster and higher-quality techniques. This evolution led to a shift in photography's role—from merely replicating reality to exploring more artistic expressions. This shift is captured in the observation that "photography began to change into something else, a something which had lost interest in the unique connection between the inside and outside."

To distinguish between ‘documentary’ and ‘artistic’ trends in architectural photography, it's important to define these terms. Documentary photography is characterized by an attempt to represent reality with minimal influence from personal feelings, biases, or subjective interpretations. In contrast, artistic photography seeks to explore the human experience, transcending mere visual accuracy to create poetic discourses on the subjective experience of space.

In the context of our study, the documentary approach to photography operates almost anonymously, producing images that serve as a future archive to illustrate the projects we studied. Using a smartphone's photographic device, we captured moments instantaneously, focusing on aspects like perspective orientation, framing balance, and distance from the subject. However, certain factors beyond our control, such as the date and time dictated by convenience rather than a consistent rule, indirectly influenced the final results. This archive proved useful when comparing different practical applications of the concepts studied in the works we visited, helping us clarify our intentions for the artistic exploration of Södra Älvsborg's project.

Photo-documentary approach to four case studies

As we continued to analyze our main case study (SÄS), we carefully observed the parallels and divergences when compared to other three cases.

SÄS - Södra Älvsborg Psychiatric Clinic, Borås, Sweden (2021) White Akitekter

Ö - Östra Psychiatric Clinic, Gothenbug, Sweden (2006) White Arkitekter

H - Nordsjælland Psychiatric Clinc, Helsingør, Denmark (2006) Julien De Smedt Architects

F - Friluftssykehuset, Oslo, Norway (2018) Snøhetta

Drawing from research in environmental psychology and our understanding of the psychological constructs of space, the primary goal of such research became evident: to gather data that informs the design of spaces promoting stress reduction and recovery. Our visits to these Scandinavian buildings provided valuable impressions that were deeply expressive of our inquiry. In our exploration of these PCS, we identified various perceptual bridges that connect the human mind with the physical environment. To better understand this concept, let's imagine these bridges as being defined by the five human senses—touch, smell, hearing, taste, and sight. Each of these bridges has a toll that acts as a mediator, allowing only certain elements of reality to pass through, based on the limitations of human perception. For example, only sounds within the range of 20Hz to 20kHz can cross the hearing bridge, and only light within the visible spectrum, between infrared and ultraviolet, can cross the vision bridge, even though other wavelengths exist beyond this range.

Photography, in particular, relies mainly on the bridge of vision. While some photographic techniques can capture UV light, the human eye can only perceive light within the visible spectrum. When photography is used for documentary purposes, the information captured through light is filtered by these perceptual tolls, resulting in a reduced range of subjective interpretation. Thus, the data captured by the camera is aligned with the human capacity for visual perception, adhering to the natural limitations of our senses.

By sticking to the metaphor of the vision bridge, we can see how photography, as a tool, provides a more objective representation of reality. This helps to minimize the influence of personal biases and subjective interpretations, making it a reliable medium for documenting and analyzing architectural spaces in our study. Through this lens, we gain a clearer understanding of how environmental factors influence human perception and, ultimately, contribute to the design of spaces that support mental well-being.

Programmatic Legibility

In examining programmatic legibility, we begin with how the design of a building guides the user's navigation through its spaces, focusing on aspects such as location, volumetry, and façade configuration. At Östra Hospital (2006), these elements that could highlight the entrance are underexplored. In contrast, Helsingør (2006) employs a more effective approach, with two distinct entrances—public and private—strategically placed at a convergence point within its star-shaped layout. Similarly, at Södra Älvsborg (2021), although the building also adopts a star shape, access is provided via an interstitial volume that connects the old and new structures. Both Södra Älvsborg and Helsingør exemplify clarity in scale and inviting morphologies, enhancing user navigation.

The user's second interaction typically occurs at the reception desk, the first internal space they encounter. At Östra, the reception's location is unclear, following a pattern of subdued entrance announcements. However, a lobby exists, guided by materiality, lighting, and decoration derived from certain PCSs. In Helsingør, the reception extends from the entrance into a public access lobby on the upper floor, with a private lobby for admitted users on the lower level, effectively balancing public and private spaces. Södra Älvsborg follows a similar distinction but achieves it through wall positioning, ceiling height variations, and furniture layout, blending relaxation with dignity and privacy.

In examining programmatic legibility, we begin with how the design of a building guides the user's navigation through its spaces, focusing on aspects such as location, volumetry, and façade configuration. At Östra Hospital (2006), these elements that could highlight the entrance are underexplored. In contrast, Helsingør (2006) employs a more effective approach, with two distinct entrances—public and private—strategically placed at a convergence point within its star-shaped layout. Similarly, at Södra Älvsborg (2021), although the building also adopts a star shape, access is provided via an interstitial volume that connects the old and new structures. Both Södra Älvsborg and Helsingør exemplify clarity in scale and inviting morphologies, enhancing user navigation.

The user's second interaction typically occurs at the reception desk, the first internal space they encounter. At Östra, the reception's location is unclear, following a pattern of subdued entrance announcements. However, a lobby exists, guided by materiality, lighting, and decoration derived from certain PCSs. In Helsingør, the reception extends from the entrance into a public access lobby on the upper floor, with a private lobby for admitted users on the lower level, effectively balancing public and private spaces. Södra Älvsborg follows a similar distinction but achieves it through wall positioning, ceiling height variations, and furniture layout, blending relaxation with dignity and privacy.

Use of Color and Light

The exploration of color and light in these spaces reveals varying approaches. At Helsingør, Friluftssykehuset, and Södra Älvsborg, zenithal light is utilized in reception areas, while Östra employs a north-facing glass façade. Östra’s corridors are punctuated by large glazed windows facing courtyards, allowing ample natural light. Helsingør’s smaller courtyards result in less dramatic lighting, and Södra Älvsborg, despite having the smallest corridors, ensures bright living spaces at each corridor’s end.

Color choices across these buildings reflect a general adherence to EBD principles, with a focus on belonging and aesthetic culture. Frederiksberg and Södra Älvsborg stand out for their appealing yet sober palettes. In contrast, Helsingør and Östra’s color schemes are less considered, occasionally veering into kitsch.

The exploration of color and light in these spaces reveals varying approaches. At Helsingør, Friluftssykehuset, and Södra Älvsborg, zenithal light is utilized in reception areas, while Östra employs a north-facing glass façade. Östra’s corridors are punctuated by large glazed windows facing courtyards, allowing ample natural light. Helsingør’s smaller courtyards result in less dramatic lighting, and Södra Älvsborg, despite having the smallest corridors, ensures bright living spaces at each corridor’s end.

Color choices across these buildings reflect a general adherence to EBD principles, with a focus on belonging and aesthetic culture. Frederiksberg and Södra Älvsborg stand out for their appealing yet sober palettes. In contrast, Helsingør and Östra’s color schemes are less considered, occasionally veering into kitsch.

Implementation of artworks

The use of artworks across these spaces varies significantly. Östra predominantly features abstract art, which recent EBD research advises against. Helsingør presents a hybrid approach, mixing abstract and figurative pieces. Södra Älvsborg, better informed by current research, predominantly showcases realistic and naturalistic art, with subtle proto-abstractionist touches. This approach aligns with the aim of psychiatric spaces to connect rather than alienate individuals, using art to foster engagement rather than surreal detachment.

Details and material choices

Material selection also plays a critical role in the design of these spaces, with varying degrees of success. Helsingør’s hyper-processed materials create cold, sterile environments, likely focused on meeting clinical regulations but lacking warmth. Östra uses more natural materials, such as wood, though not consistently, leading to a mix of successes and failures depending on the area. Södra Älvsborg, however, stands out by learning from its predecessors’ mistakes. It combines compliance with regulations with thoughtful material choices, such as CLT, stone floors, wood paneling, and effective acoustic solutions, creating spaces that feel both robust and familiar.

The use of artworks across these spaces varies significantly. Östra predominantly features abstract art, which recent EBD research advises against. Helsingør presents a hybrid approach, mixing abstract and figurative pieces. Södra Älvsborg, better informed by current research, predominantly showcases realistic and naturalistic art, with subtle proto-abstractionist touches. This approach aligns with the aim of psychiatric spaces to connect rather than alienate individuals, using art to foster engagement rather than surreal detachment.

Details and material choices

Material selection also plays a critical role in the design of these spaces, with varying degrees of success. Helsingør’s hyper-processed materials create cold, sterile environments, likely focused on meeting clinical regulations but lacking warmth. Östra uses more natural materials, such as wood, though not consistently, leading to a mix of successes and failures depending on the area. Södra Älvsborg, however, stands out by learning from its predecessors’ mistakes. It combines compliance with regulations with thoughtful material choices, such as CLT, stone floors, wood paneling, and effective acoustic solutions, creating spaces that feel both robust and familiar.

Relationship between interior and exterior spaces

The relationship between interior and exterior spaces varies across the buildings. Östra features fully enclosed internal courtyards with artificial nature, creating a somewhat introverted environment. Södra Älvsborg offers a hybrid solution, with courtyards and semi-open gardens, providing a balance between safety and a sense of autonomy for patients. Both Södra Älvsborg and Helsingør provide rooms with access to outdoor balconies, with Helsingør also offering a connection to a lakeside space, combining internal patios with a more generous natural environment.

Nature's participation

Finally, the role of natural environments in these spaces is critical. Östra’s connection to nature is primarily through its internal courtyards, making it the most introverted of the cases. Frederiksberg offers the most open engagement with nature, actively encouraging users to benefit from natural surroundings. Helsingør provides controlled yet free access to a lakeside area, promoting autonomy. Södra Älvsborg, while providing visual access to a nearby forest, allows physical access only when the patient’s condition permits, emphasizing a cautious yet supportive approach to incorporating nature into the therapeutic environment.

The relationship between interior and exterior spaces varies across the buildings. Östra features fully enclosed internal courtyards with artificial nature, creating a somewhat introverted environment. Södra Älvsborg offers a hybrid solution, with courtyards and semi-open gardens, providing a balance between safety and a sense of autonomy for patients. Both Södra Älvsborg and Helsingør provide rooms with access to outdoor balconies, with Helsingør also offering a connection to a lakeside space, combining internal patios with a more generous natural environment.

Nature's participation

Finally, the role of natural environments in these spaces is critical. Östra’s connection to nature is primarily through its internal courtyards, making it the most introverted of the cases. Frederiksberg offers the most open engagement with nature, actively encouraging users to benefit from natural surroundings. Helsingør provides controlled yet free access to a lakeside area, promoting autonomy. Södra Älvsborg, while providing visual access to a nearby forest, allows physical access only when the patient’s condition permits, emphasizing a cautious yet supportive approach to incorporating nature into the therapeutic environment.

In the forest of Borås

The notion that “we like to be out in nature so much because it has no opinion about us” - expressed by 19th century philosopher Friederich Nietzsche - underscores a significant aspect of the interaction between humans and natural environments. This sentiment became vividly manifest during our first visit to the Borås forest, where the profound benefits of a brief immersion in a largely untouched natural space were experienced firsthand. Here, through this intense experience, we wrote that “as mental health therapist one should behave like a forest”. This thought, at the time unkowingly similar to that of Nietzsche, served as a foundational metaphor towards a further investigation about what could be capable of attempting to document such phenomena.

The experience was not only motivational but also instrumental in shaping the approach to capturing the forest's impact through photography. Despite the inherent subjectivity in the photographic medium, the resulting images effectively convey the transformative influence of the forest on mental states.

“Being ourselves no will nor fate can solve

So we accept the effort. I dream or act,”

This poem by Fernando Pessoa resonates with the intense transformative experience felt in this forest. This literary reflection, bearing in it a poetic caesura, reinforced the desire to express the experience through an artistic lens, aligning with the phenomenological insights gained during the visit.

Having accessed this forest as one side of the caesura, the date awaited us when we would have to revisit the clinic to access the interior of the rooms orientated towards both this nature and the aesthetically neglected hospital building. We concluded the photo-documentary approach to these cases, which, although it helped us understand and apply PCS in practice, also left us wondering how close we had come to what we were looking for (the dialogue between the human mind and the external environment), and whether it could live on in another kind of approach, for which “... to photograph with attention is to look and think, to open a door between what can be seen directly and what is hidden and can only be imagined.”

A significant discussion with Stefan Lundi in Gothenburg highlighted the potential of integrating art into research methodologies. Despite his extensive experience, Lundi admitted that he had not found satisfactory answers regarding the role of art in empirical research. Nevertheless, he supported the idea that “art as a complement to empirical data could potentially shake up stagnated discourses in the direction of new discoveries.”