II - Photographing the experience of therapeutic space

Art as a tool for broadening interpretation

The investigation into artistic motivation and its psychological underpinnings led to a significant encounter with the work of Austrian psychoanalyst and philosopher Otto Rank. Rank’s exploration of the internal psychological processes behind artistic creation provides a framework for understanding the motivations that guided this study. He identified three types of artists across different historical periods:

i. The primitive artist representing a collective ideology, this artist’s work embodies an abstraction that seeks the divine through the concept of the soul.

ii. The classic artist rooted in the social concept of art, this artist’s expression is defined by idealism, with beauty as its purest form.

iii. The modern artist centered on the individual concept of genius, this artist is driven by personal self-realization.

In contemporary times, the modern artist's tendency to infuse their personal life into their creative work raises a critical question: Does this focus on personal experience risk reducing art to a mere aesthetic exercise devoid of deeper meaning? This concern may be fundamentally psychological, revealing significant connections between personal experience-driven art and ideology-driven art, despite their differing essences. The artistic research proposed here aligns with modern art principles, where the artist expresses personal life experiences alongside ideological interests, in this case, advocating for the design of quality spaces that uphold human dignity.

The impetus for artistic expression in this study stems from a personal encounter with a family member, symbolically explored through visits to the Södra Älvsborg Clinic and Borås forest. This experience underscores the intention to address deeper meanings through artistic creation.

Art, as stated by Elizsabeth Grosz, "provokes a thirst for reason, for the kinds of knowledge science produces, although it is never content to turn itself into science, that is, to decorporealize itself." The creation of an artistic object aims to influence the range of interpretations and meanings in the debate. Artistic expression, derived from subjective experiences, employs photography to simulate human perception. Experiencing a place involves more than just the visual spectrum; it includes dimensions beyond the measurable, such as intuition, dreams, symbolic creation, and active imagination. This perspective is akin to the fascination of childhood or the imaginative spirit of Don Quixote, unshaken by external doubts. Clare Cooper’s observation that “perhaps it is the so-called normal adult who, having been socialized to regard self and environment as separate and totally different, is most out of touch with the essential reality of oneness with the environment” highlights a dimension of human experience often neglected in Environmental Psychology analysis. This study aims to address these dimensions by exploring their roles in therapeutic space design.

Art, as stated by Elizsabeth Grosz, "provokes a thirst for reason, for the kinds of knowledge science produces, although it is never content to turn itself into science, that is, to decorporealize itself." The creation of an artistic object aims to influence the range of interpretations and meanings in the debate. Artistic expression, derived from subjective experiences, employs photography to simulate human perception. Experiencing a place involves more than just the visual spectrum; it includes dimensions beyond the measurable, such as intuition, dreams, symbolic creation, and active imagination. This perspective is akin to the fascination of childhood or the imaginative spirit of Don Quixote, unshaken by external doubts. Clare Cooper’s observation that “perhaps it is the so-called normal adult who, having been socialized to regard self and environment as separate and totally different, is most out of touch with the essential reality of oneness with the environment” highlights a dimension of human experience often neglected in Environmental Psychology analysis. This study aims to address these dimensions by exploring their roles in therapeutic space design.

When approached through phenomenology, the analysis of the perceptive act suggests that there are immeasurable dimensions of reality influence the measurable ones. As Steven Holl articulates, “Perception and cognition balance the volumetrics of architectural spaces with the understanding of time itself. An ecstatic architecture of the immeasurable emerges.” This understanding extends itself to the role of nature in its ability to foster senses of belonging, appreciation, contemplation, and serenity. Hence explorations in this chapter will consider how varying degrees of permeability between external natural environments and internal human experience can dialogue between each other through architectural space.

Phenomenological approach to the person-environment studies

The continuous dialogue between self and environment, as articulated, underscores the inseparability of individual identity from spatial and situational contexts. This concept was vividly illustrated during an exploration of Borås forest, where the interaction between matter and psyche became apparent. Building on an in-depth study of the PCS and key principles of Phenomenology of Space, a conceptual and methodological framework is proposed to guide photography and its subsequent analysis.

In Phenomenology, ambiguity is embraced as a strength rather than a limitation. It serves as a dialectical tool, encouraging open-ended inquiry rather than definitive proof or disproof. This approach fosters exploration of uncharted territories, highlighting the potential for art objects to uncover new perspectives. Phenomenology, in the context of ‘person-space’ studies, offers a significant contribution by focusing on subjective human experiences of space. This philosophical movement explores and describes phenomena derived from human experience, aiming not only to document idiosyncratic descriptions but also to uncover the essence of those phenomena. The phenomenological method embraces uncertainty and spontaneity, allowing for creative development and methodological fluidity.

The proposed approach involves more than just selecting a method; it encompasses the entire research process. This approach includes defining starting points, providing detailed descriptions of experiences, and formulating relevant questions. The term ‘approach’ is thus preferred over ‘method’ to encompass this broader, principle-guided process. The concept of ‘lifespace’ illustrates that the space we inhabit is not merely a backdrop for our actions but actively influences and interacts with us. This perspective aligns with hermeneutic analysis, which emphasizes uncovering meanings within tangible objects or expressions, such as photographs, without overloading them with extraneous explanations. Phenomenological analysis encourages subjective evaluation, where intuition plays a crucial role. Drawing on the work of Itzhak Bentov and Rollo May, intuition is viewed as a form of hidden knowledge rather than mere chance. This intuitive process enhances the interpretative value of the phenomenological approach, extending beyond intellectual and emotional responses.

The chance encounter with Lisbeth Funck during an exchange period with AHO in 2021 introduced a fresh perspective on spatial conception through architectural theory. The art-based research methodology of her doctoral thesis presented artefacts expressive of experiences from three case studies, including models, sculptures, paintings, and photographs. Funck’s emphasis on the phenomenological approach to space, particularly through the concept of abstracted space, informs the current study and offers a framework for understanding the spatial experience in a new light.

About the ‘dialogue between’

Lisbeth Funck's analysis emphasizes that for the phenomenon of abstracted space to be truly experienced, two primary conditions must be met: (i) buildings must be perceived as autonomous entities, and (ii) the ontological nature of Becoming must be recognized, acknowledging their constant states of change. This perspective shifts the focus from viewing buildings and their techniques merely as representations to understanding them as material compositions through which character-driven expressions can flow. Brian Massumi’s discussion of affective experience supports this view, suggesting that corporeal-sensory presence is pre-consciously indicated before the propensity to affect. Therefore, total immersion in the phenomenon, rather than partial engagement, is crucial.

Funck’s work posits that through interaction, one ‘becomes the matter’ with which they engage. Building on these insights, our approach integrates phenomenology to develop a conceptual and methodological framework for analyzing spatial experiences. By merging Funck's concept of ‘the abstracted space’ with our notion of ‘caesura’ we seek to explore the evocative and interpretative potential inherent in both.

The dialogue between matter and psyche is central to this exploration. Matter, as the measurable aspect of our environment, and psyche, as the immeasurable internal experience, interact in a reciprocal manner. This dynamic goes beyond a simple monologue from the individual to the space, and instead it involves a mutual interaction where both architectural spaces and human individuals embody aspects of matter and psyche simultaneously.

The term ‘psyche,’ derived from the Greek ψυχή (psychí), implies an animistic essence inherent in all things, suggesting that our research aims to bridge the experience of a place’s essence with its external environment. Sarah Robinson’s concept of the ‘resonant body’ in her book ‘Architecture as a Verb’ provides further insight. Robinson, through neuroscientific analysis, defines the resonant body as one attuned to the rhythms of its surroundings. This aligns with Cognition 4E, which views consciousness as an emergent property of interactions with the world, rather than an isolated phenomenon within the individual.

In applying these ideas, we analyzed abstracted spaces captured by Funck’s photography, which offered clues for an artistic strategy to perceive and convey spatial phenomena. Our subsequent visit to Friluftssykehuset in Oslo involved a conscious examination of the spaces, their interaction with the environment, and the detailed material solutions. This experience revealed how nature’s reflection through windows imbued the shelter’s interior with a sense of new reality, akin to Funck’s work.

Our engagement with both the forest of Borås and Friluftssykehuset reflects a deeper understanding of how space, made of matter and psyche, merges into a singular dimension in memorable architectural experiences. This fusion allows for identification with the space and moment, demonstrating architecture’s role in reconciling oneself with the world through sensory mediation. The interplay of these dimensions enriches our comprehension of architectural and spatial experiences, emphasizing the profound connection between environment and individual consciousness.

Gradations of permeability between spaces

In the series of photographs taken of the shelter, the aim was to illustrate the visible thresholds between the external forest environment and the internal space of the shelter. By capturing the reflections in the windows, the photographs sought to evoke visual narratives that reflect the dialogue between these two realms. This exploration echoed the theoretical and practical insights gained during classes with Professors Lisbeth Funck and Matthew Anderson, where the concept of spatial permeability was examined in depth through personal and theoretical inquiries. A written passage from that project’s research that encapsulates the experience of serenity through expansion of the Self:

“Nature brings me closer to It once again.

I am no longer myself as my Self.

I Am entirely with the immensity of existence surrounding me,

as 'I' become 'We', my inner distress is attenuated.”

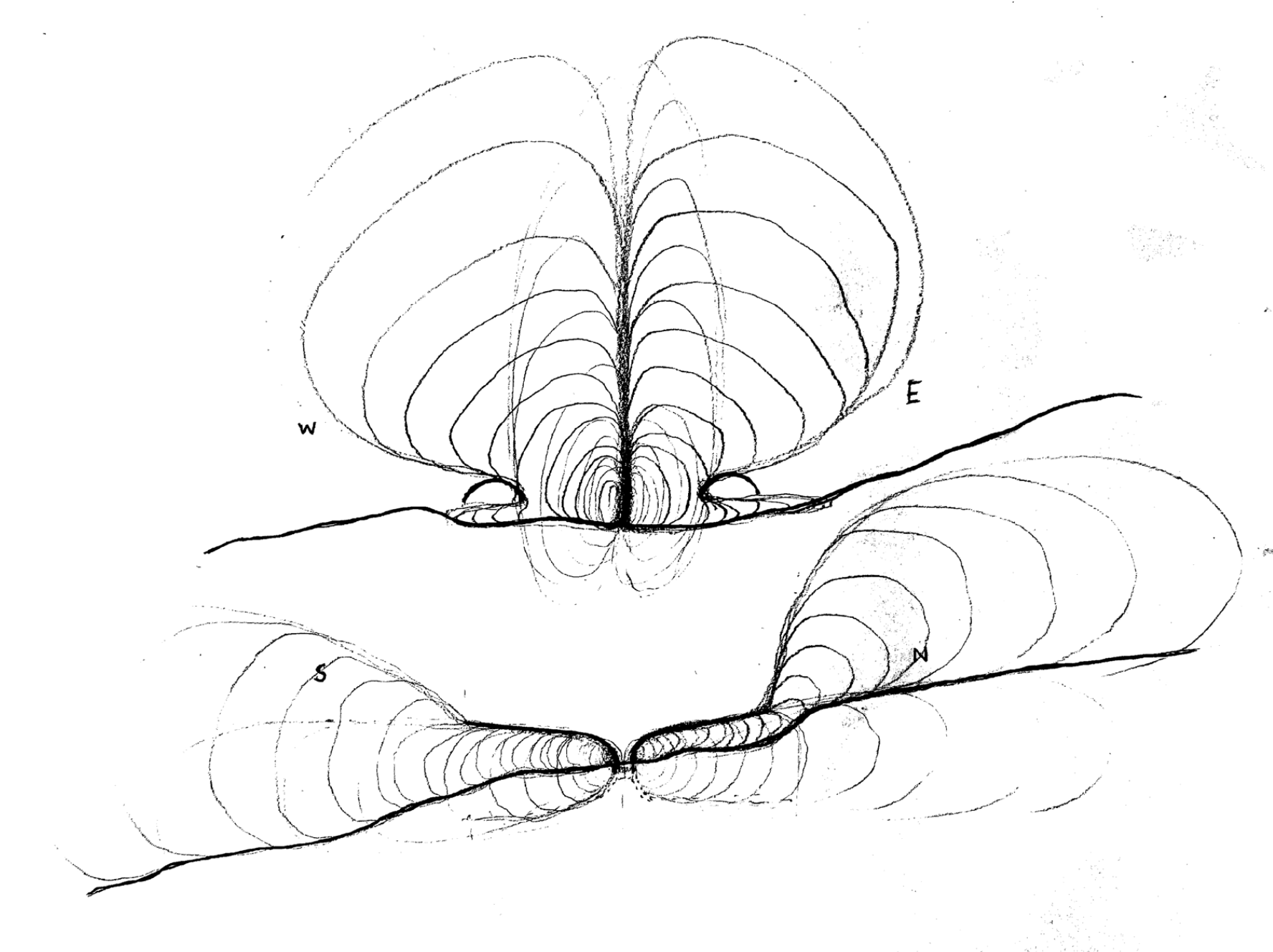

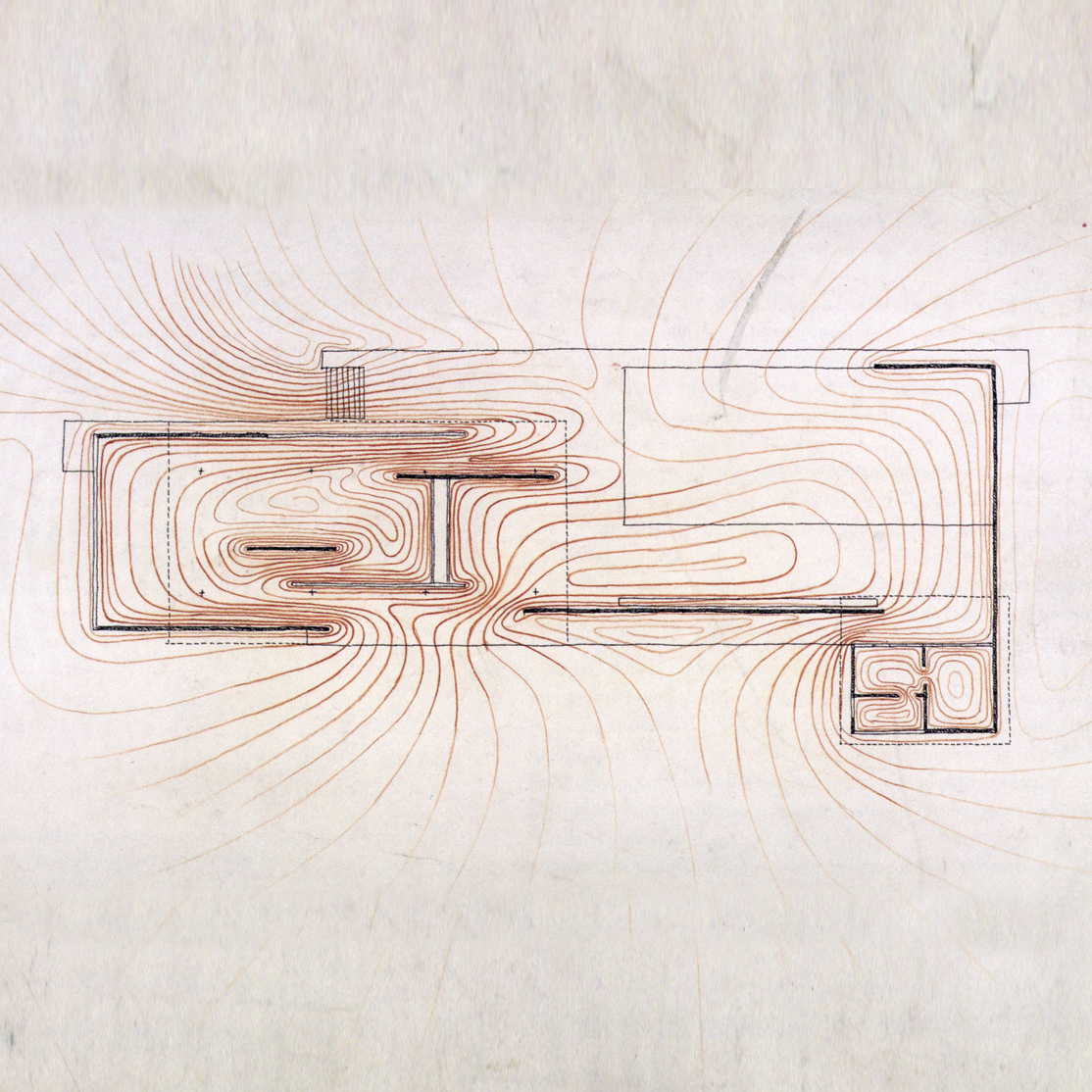

This sentiment parallels our exploration of spatial permeability, akin to early sketches of the Farnsworth House by Professor Manuel Soares and Paul Rudolph's drawings of the Barcelona Pavilion. These works, alongside our previous study of Mies van der Rohe’s Patio Houses, emphasize the architectural elements of permeability (windows) versus impermeability (walls). Mies van der Rohe’s design principles highlight the contrast between these elements, contributing to our understanding of spatial fluidity. Paul Rudolph's drawings, in particular, seek to express the internal dynamics of space that, while not directly measurable, are perceptible to the artist. These drawings exemplify how space and individual experience interact, blending the materiality of the built environment with the psyche’s interpretation of spatial essence. This approach aligns with our philosophical framework, which extends beyond visual perception to encompass tactile and auditory experiences.

Our inquiry into Professor Lisbeth Funck’s doctoral dissertation led to an informal discussion in an Oslo café, where we explored the connections between our work and hers. During this conversation, we discussed future research directions and received references to relevant works, including those by Japanese architect Hiroshi Nakao. Nakao’s projects, like Paul Rudolph’s, also explore qualitative aspects of spatial permeability. Nakao’s ‘Black Maria’ project involves an adaptable architectural space that examines the interface between interior and exterior, highlighting the impact of spatial configurations on their surroundings. Another project, the ‘Dark Box Bird Cage,’ features wooden walls painted black. Over time, the sun’s exposure lightens parts of the paint, creating permanent marks that reveal the interaction between the architectural object and its environment. These projects demonstrate how light’s interaction with material qualities can visually manifest the permeability of a given space.

Participation of space in the act of photography

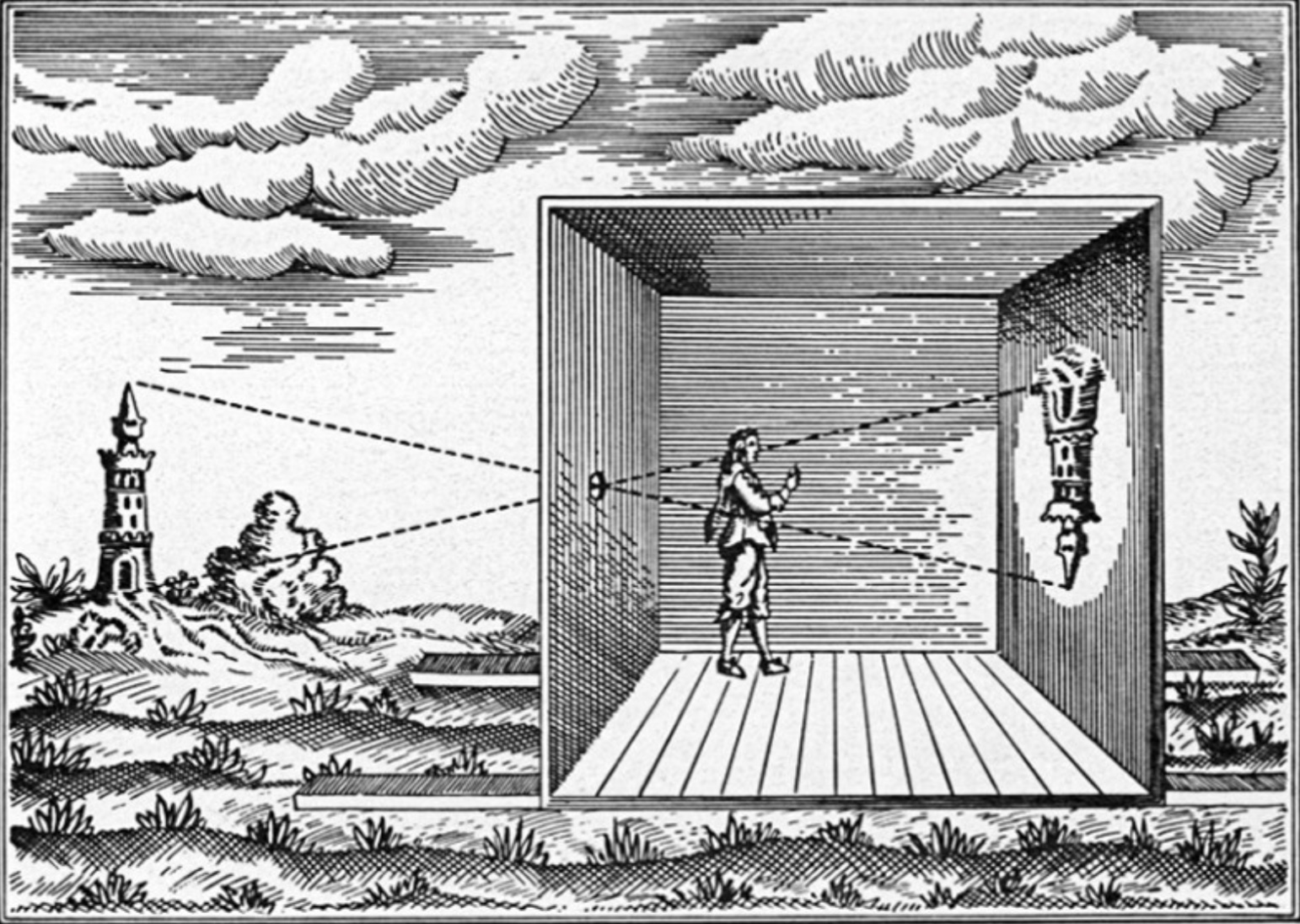

In an experiment broadcast on the National Geographic television channel, which we encountered seven years ago and which has since served as a reference in our research, we observed a distinct mode of interaction between interior and exterior spaces, facilitated by the properties of light permeability. This interaction was demonstrated through the camera obscura phenomenon, wherein a single aperture was placed in the center of an opaque black plastic sheet that covered an entire window. The result was an inverted projection of the exterior environment within the space, a phenomenon governed by the laws of rectilinear light propagation. Parallel to this experiment, we engaged with the work of contemporary Cuban artist Aberaldo Morell, who has been transforming spaces into camera obscuras since 1991, capturing the interplay between interior and exterior in large-format photography. Morell's work refines our understanding of this ancient light-capturing technique, offering a robust conceptual framework that translates the dialogue between interior and exterior spaces.

These approaches resonate with the concept of the ‘abstracted space’, particularly the idea that "buildings should be considered autonomous entities." By acknowledging the autonomy of space from a phenomenological perspective, we move towards personifying space and attributing it with animistic qualities (psyche). This personification allows for the possibility of considering space as a subject capable of self-expression.

Further research, particularly in Environmental Psychology (EP), often explores space through the active involvement of its users, a method that informs the understanding of space from the context of psychiatric hospitalization. As Ellie Byrne notes, "a therapeutic landscape can be perceived as not only the physical environment and its impact on the individual, but also the complex web of inter-personal relations, power structures, cultural norms, and symbols associated with a particular setting." This perspective underpins our objective of using art to reveal the therapeutic dimensions inherent in the interaction between individuals and healthcare spaces. Photography, in this context, emerges as a valuable tool for participant-based research methods, as evidenced by Byrne's work. In her study, photography serves as a source of qualitative visual data, contributing to a deeper understanding of psychiatric spaces. Byrne's methodology involved providing patients with disposable cameras to document moments within the space that influenced their treatment experiences. Subsequent interviews with the participants highlighted the essential interdependence of textual testimonies and photographs, aligning with her research approach.

In our case, however, the research question diverges due to the phenomenological nature of our approach, as articulated at the beginning of this chapter: "... to avoid overloading the results with too many explanations about the significance of their realization process, but rather to find ways of uncovering meanings through the work itself."

Our proposal to transform the rooms of the SÄS clinic into autonomous entities that express their psyche — affected by their position, orientation, and levels of visual/light permeability with the outside world — is an endeavor to create a testimony governed by the rooms' ontological qualities. This testimony is not communicated through words but is instead expressed through the architectural conditions of these spaces.

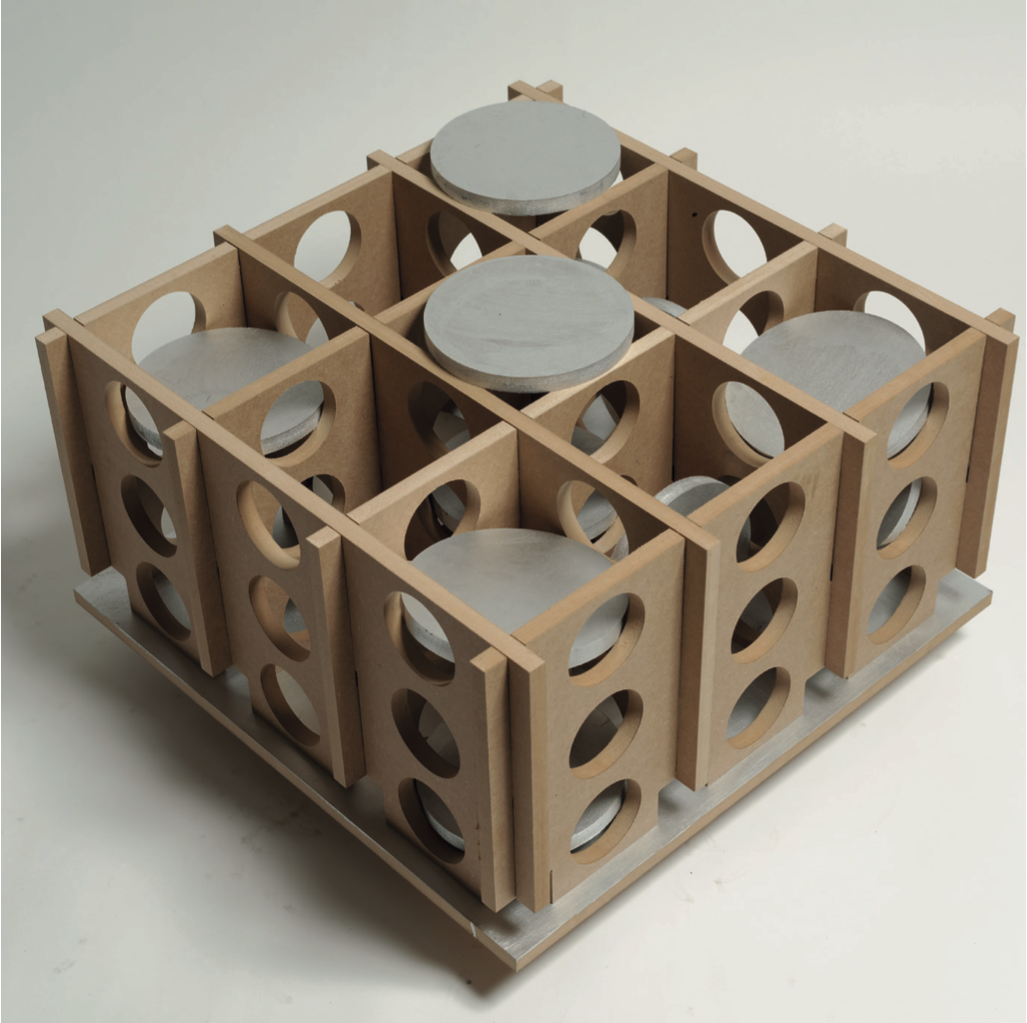

Therefore, to analyze this expression in a manner consistent with the conditions that dictate it, it was necessary to ensure that the captured photograph could be experienced in the three dimensions that define the room at the time of its capture. This requirement led us to reject the expression of the camera obscura phenomenon as employed by Morell and National Geographic, as it would only end up producing a two-dimensional photograph of a three-dimensional phenomenon. Instead, our approach seeks to utilize the three-dimensional characteristics of the space—its position, size, and the distance between walls, ceiling, floor, and windows—to engage the observer's sense of abstraction, simulating the process of architectural perception in a photograph much like an architectural model does.

Of the Latent Potential in the Pinhole Model

During our academic tenure at the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Porto (FAUP), we engaged with the architectural model as a critical tool for design exploration. This maquette, with its capacity to transport the observer into a simulated three-dimensional reality through analog means, offers a distinct experiential advantage over its digital counterpart, which relies on computer-modeled spaces. The analog model allows for direct engagement with the human senses of sight and touch, enabling an act of abstraction that depends largely on the observer’s imaginative capacity and spatial awareness, rather than being defined by perceptual preconditions imposed by digital programs. While digital methods undoubtedly have their utility in simulating space, they did not align with the expressive intent central to our inquiry in this instance.

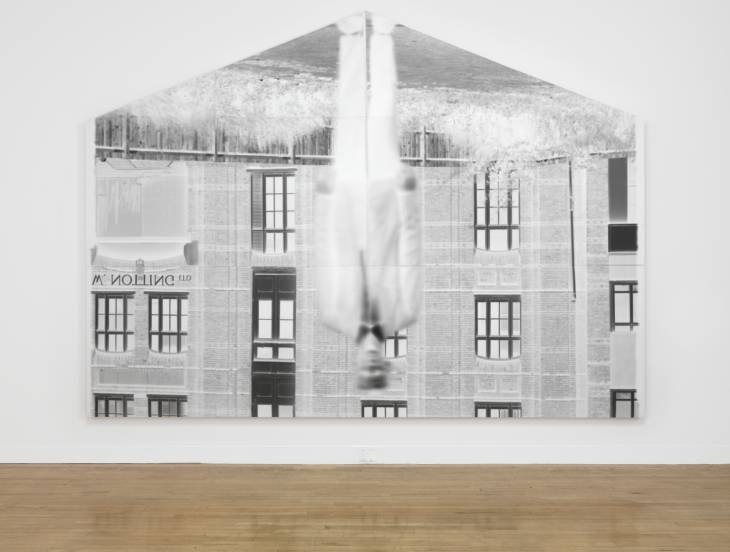

The relevance of this approach is further illuminated through the work of English artist and photographer Steven Pippin. Pippin's oeuvre is characterized by his innovative use of kinetic sculptures and improvised mechanisms derived from everyday objects repurposed as photographic equipment. His initial experiments, which involved converting furniture and other common items into pinhole cameras, resonate with the exploratory ethos observed in Justin Quinnell's highly experimental body of work with pinhole photography. Among Pippin's projects, Self-Portrait Made Using a House Converted into Pinhole Camera stands out as particularly instructive. In this work, Pippin transformed a prefabricated bungalow in London into a pinhole camera, lining the interior wall opposite the door with photosensitive paper. Through a small aperture drilled in the door, he allowed the camera obscura effect to take place, capturing an image of himself as he stood before it for eight hours. The final composition, composed of several sheets of photosensitive paper left in their original photo-negative state, represents a compelling example of space actively participating in the photographic process, rather than merely serving as a backdrop for the camera obscura phenomenon.

Pippin's work exemplifies a shift from passive to active spatial engagement in photography. Unlike conventional camera obscura examples, such as those by Aberaldo Morell and National Geographic, where space passively submits to the luminous phenomenon, Pippin’s approach confers a degree of autonomy to the architectural space. By affixing photosensitive paper to the wall, Pippin empowered the space to actively contribute to the photographic outcome.

Transposing Pippin’s method directly to our case, however, presented significant logistical challenges, particularly in terms of repetition, reproducibility, and transport—issues central to our study at SÄS. Our objective was to represent the gradient between natural and artificial light, which necessitated capturing the external environment through multiple rooms' windows. While producing photographs in the actual space at a 1:1 scale was not entirely out of the question, the practical constraints and likely resistance to such an ambitious undertaking rendered it impractical.

Although we had previously employed multi-exposure techniques with conventional digital and analog cameras, we had yet to explore their implications within the context of pinhole photography. Janet Neuhauser’s extensive work with pinhole cameras featuring multiple apertures, which allows for overlapping perspectives on the same subject, suggests the practicality of this technique and reveals the unique expressive qualities it can yield.

Although we had previously employed multi-exposure techniques with conventional digital and analog cameras, we had yet to explore their implications within the context of pinhole photography. Janet Neuhauser’s extensive work with pinhole cameras featuring multiple apertures, which allows for overlapping perspectives on the same subject, suggests the practicality of this technique and reveals the unique expressive qualities it can yield.